Assahafa.com

In a significant revelation about Morocco’s linguistic landscape, High Commissioner for Planning Chakib Benmoussa announced that while 92% of Moroccans speak Darija (Moroccan Arabic), only 25% of the population speaks Amazigh, Morocco’s second official language.

This statement comes amid growing concerns about the preservation of the indigenous language and its implementation in the education system.

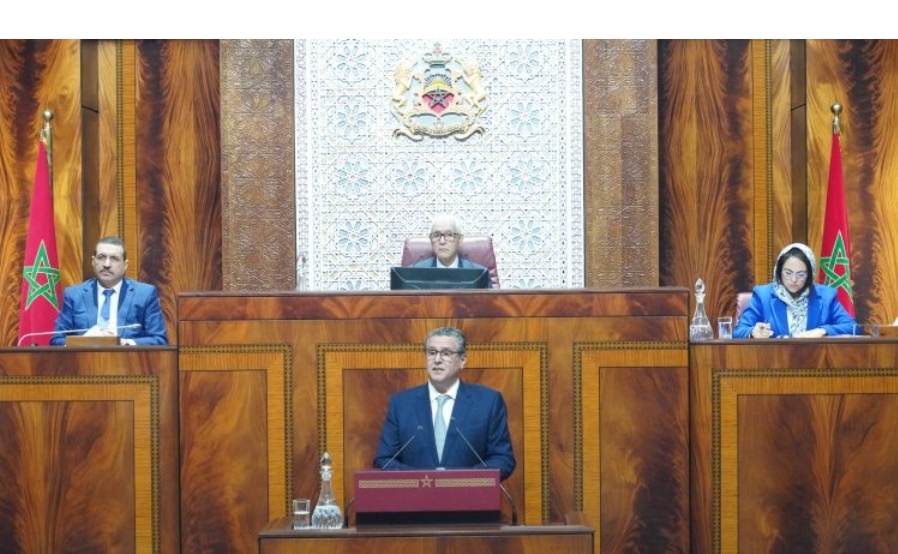

Speaking today at a press conference presenting the detailed results of the 2024 General Census of Population and Housing (RGPH), Benmoussa highlighted that Arabic remains the most widely used language in Morocco, with particular emphasis on the use of Hassaniya in the southern provinces.

The census data also showed a notable increase in the population’s ability to read and write foreign languages, particularly French and English.

However, these figures stand in stark contrast to claims by Amazigh associations, who strongly contest the official numbers and assert that up to 85% of Moroccans speak Amazigh, potentially representing 29.6 million out of the total population of 37 million.

This stark and lethal discrepancy, seen by some activists as an attempt to undermine Amazigh identity, recalls the post-independence “Arabization” policies of the 1950s when the newly independent state adopted Arabic as the main language, marginalizing Tamazight despite Amazigh areas having spearheaded the armed struggle for independence from France.

The status of Amazigh in Morocco has evolved significantly over the decades. A turning point came in 2001 when King Mohammed VI delivered a historic speech in Agadir, affirming that Amazigh belongs to all Moroccans and is a fundamental element of Moroccan culture.

This led to the establishment of the Royal Institute of Amazigh Culture (IRCAM). In 2003, Morocco officially adopted the Tifinagh script, culminating in the recognition of Tamazight as an official language in the 2011 Constitution amid Arab Spring protests.

However, the 2024 census itself has sparked controversy over its treatment of Tamazight. The Moroccan Association for Research and Cultural Exchange (AMREC) has strongly criticized the High Commission for Planning (HCP) for “systematic exclusion of Tamazight” in the census process.

AMREC said Amazigh civil society, experts, and researchers were not involved in designing the questionnaire, and that the HCP deliberately marginalized Tamazight in its communication campaign.

Several Amazigh organizations expected a repeat of the 2014 census, where Tamazight speakers were reported at just 27% of the population, a figure they strongly contest – and that appears to be the case with Benmoussa’s latest announcement.

In response, Ahmed Lahlimi Alami, ex-High Commissioner for Planning, defended the census as a “sovereign operation with a national dimension,” stating that Tamazight and its main dialects are included in the questionnaire.

He explained that households are asked whether they “speak a special local dialect,” emphasizing that the census is not an ethnic or tribal count because “everyone is Moroccan.”

Despite the constitutional milestone of 2011, implementation challenges persist. Ahmed Assid, a human rights activist and Amazigh writer, notes in an interview with Reuters that “Amazigh language lost two thirds of its speakers in five decades,” highlighting the urgent need for preservation efforts.

The challenge is particularly acute in urban areas, where many families have lost their connection to the language.

In an interview with Global Voices, Abdellah Bouzndag, an expert at the Royal Institute of Amazigh Culture, emphasizes the broader implications of language access: “Access to information is a fundamental right for Amazigh speakers nationwide, acknowledged by all international human rights conventions. Unfortunately, it is often inadequately provided in government and public services.”

When he was the minister of education, Benmoussa outlined ambitious plans to expand Amazigh language education, announcing a 50% increase in teaching positions with 600 spots available for the current training season.

“All Moroccan children will study the Amazigh language starting in 2029,” Benmoussa declared, detailing that 478 candidates have already passed recruitment exams for specializing in the language.

The ministry’s roadmap aims to achieve 50% coverage of Amazigh language teaching by 2025-2026, expanding from the current 1,803 primary schools (930 urban and 873 rural) to 12,000 institutions by 2030.

At present, the language is taught in 16,529 classrooms by 1,860 specialized teachers, reaching approximately 746,000 students – just 19.5% of primary school students.

The expansion plans could potentially benefit four million students, supported by recent curriculum enhancements, new textbooks, and additional cultural and historical content developed between 2020 and 2023.

Despite these initiatives and the fact that current coverage represents 31% of primary education institutions, challenges remain in implementing Amazigh across various sectors of public life.

While road signs now display Tifinagh script alongside Arabic and French, and some progress has been made in integrating the language into the judicial system, many native speakers still face difficulties accessing public services and participating fully in civic life.

The government’s commitment to preserving and promoting Amazigh culture was further demonstrated in 2023 when Morocco officially recognized Yennayer, the Amazigh New Year, as a national holiday.

However, activists continue to push for more comprehensive implementation of language rights and equal access to services for Amazigh speakers.

Source: Morocco word news